When I visit lacquerware producing regions around Japan, I often hear the word “nushi“, or lacquer artisan – literally, those who apply lacquer. However there are many other specialized craftsmen involved in the production of lacquerware. Kijishi (literally, master woodworkers) are craftmen who work with hardwoods, using special tools called rokuro, or turning wheels, to make trays, bowls, and such; while those who add decorative finishes by drawing designs with lacquer and gold or silver powder are called “makieshi“.

Hearing those traditional names still in use today for these specialized craftsmen gives a sense of how important these traditions remain, but also of the differences among them. Indeed in the past within this industry there used to be a kind of hierarchy among these roles, with those who perform the latter steps being more highly regarded. For me, each one of them is very interesting… but while “kijishi” and “makieshi” both sound good, somehow “nushi” sounds even more dignified. Many nushi work in agura style, sitting cross-legged on tatami mats, so perhaps it is this very Japanese appearance that makes it seem even more classical.

Just as with ceramics, there are certain areas in Japan which are well known for lacquerware production. Most Japanese probably have heard of Wajima-nuri and Yamanaka-shikki at least once, but there are also Echizen-shikki, Negoro-nuri, Kiso-shikki, Tsugaru-shikki, and more. In order to create lacquerware, it is essential to be in an environment with a moderate level of moisture to ensure the lacquer dries properly. Even among these, though, different places have created their own unique styles and expressions: Yamanaka lacquerware uses lighter layers of lacquer that emphasize the beauty of the natural grain of the wood, whereas Wajima artisans apply layer after layer of lacquer, and Takaoka artisans specialize in a method called raden, which inlays extremely thin slices of shells or mother of pearl.

There are nushi in every lacquer-producing area, of course; but the image that comes first to my mind when I hear the word “nushi” is Wajima in Ishikawa Prefecture. Wajima-nuri requires an amazing amount of work, first pasting fabric onto the base, then applying layer after layer of lacquer. This time-consuming nature of Wajima-nuri work sits in polar opposition from our modern efficiency-driven society, but its glossy expressions and the texture of their work are still so artistic. Mr. Shioji, a nushi in Wajima, once told me that while he would leave the base coating to other craftsmen, he would never allow anyone but himself to do the finishing work. I was very impressed with his comment, which I think showed his commitment as a nushi not only in his craft but in the way he lives as well.

One of the things I have come to realize through exploring Japanese crafts is that Japanese people are often very good at making things which require a great deal of patient and careful attention, and where the more time and care one puts in, the more beautiful the result would be. The work of Wajima nushi is probably the best example of this. But be sure to take a look at the work of nushi from other lacquerware production areas as well. No matter where they are made, lacquerware bowls are made with deep consideration for how they will feel when you hold them in your hands. This becomes a very special moment, when you can truly feel the work of nushi both literally and figuratively.

Text: Yusuke Shibata

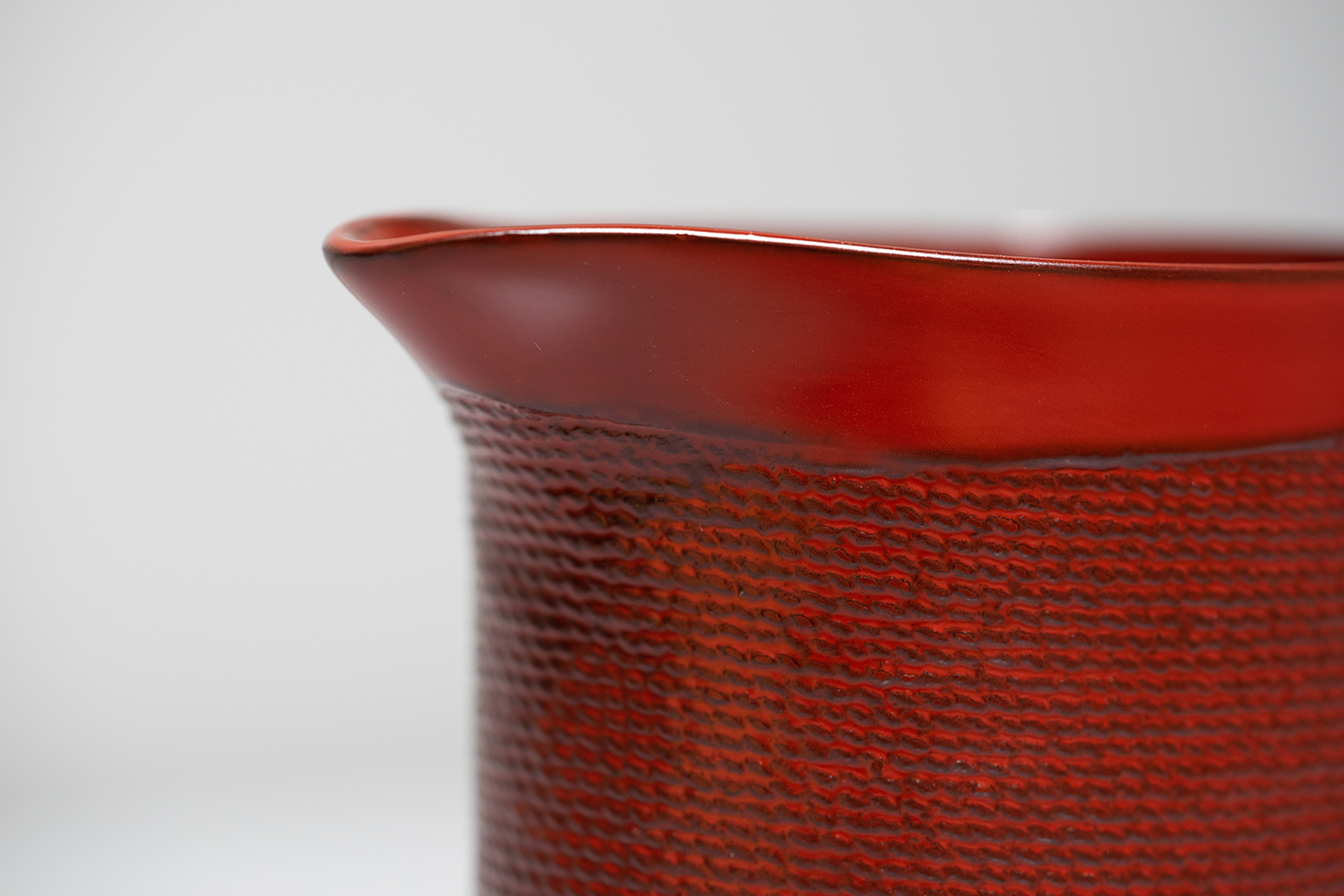

Work: Kinshi Katakuchi (Fine Line Sake Server)/Guinomi (Sake Cup) (Vermilion) by Tohachiya